Interview with Luciana Genro, PSOL/MES

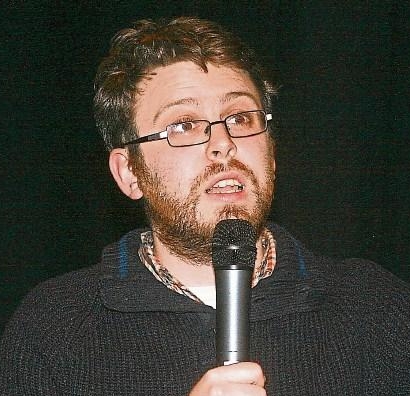

Cian Prendiville, member of RISE and PBP in Ireland spoke with Luciana Genro

This partial interview transcript has been edited for clarity and conciseness. You can listen to the full audio of the interview, tinyurl.com/RuptureRadioBrazil

Brazil’s far-right president Bolsonaro has been defeated, beaten in the recent election by center-left candidate Lula da Silva of the Workers’ Party (PT). Cian interviewed Brazilian socialist MP Luciana Genro to discuss Bolsonaro’s time in power, how he was beaten, what Lula’s government will bring, and what the socialist left is doing to continue the fight against Bolsonarism. Luciana is a leading member of the Party of Socialism and Liberty (PSOL), a pluralist socialist party in Brazil, and she is part of the Marxist group Socialist Left Movement (MES) within that.

Bolsonaro was just defeated by Lula in the recent presidential election, but it was a very close result. Closer than a lot of people were expecting, at least internationally – 50.9 percent to 49.1 percent.

Yes, Bolsonaro was defeated by around two million votes which is very, very close – less than two percent of the votes.

Could you give us a taste of what life has been like under Bolsonaro these last four years? What kinds of policies has he adopted?

Well, first, we have been in a very deep social and economic crisis since 2014. The pandemic made it worse, but it’s been happening for years. We have an unemployment rate of above 11 percent, with more than 11 million people unemployed. Underemployment affects 23 percent of the population. Jobs are low-quality and many of them are precarious. A survey carried out during the pandemic showed that 20 percent of the population doesn’t have enough food. Homelessness increased 31 percent in São Paulo over the two years of the pandemic.

At the same time, Bolsonaro made fun of the people that were dying with Covid. He despised science, despised the use of masks, despised the vaccine.

He increased the destruction of the Amazon rainforest and the expansion of agricultural frontiers, the poisoning of the soil, etc., by cutting monitoring and enforcement of the environmental laws.

This article was first published in our Reform & Revolution magazine #10. Get a subscription and support Reform & Revolution – a Marxist Caucus in DSA!

The destruction of the environment, the Covid policy, and so on – this all sounds very reminiscent of Trump.

Bolsonaro is part of the same phenomenon as Trump – an extreme far right that wants to cut the liberty and democratic freedom of the country. He has said openly that he’s in favor of torture, in favor of dictatorship.

He’s a completely authoritarian person, but he couldn’t implement a dictatorship in Brazil, because he didn’t have enough strength, and because the bourgeoisie did not entirely cooperate with him. The most important Brazilian TV network, Rede Globo, was in opposition to him, for example. So, he couldn’t do everything that he wanted to do, but with a second term, he might have gone further.

It sounds from the statistics you mentioned like he also failed to deliver economic improvements for ordinary people. But how did he manage, then, to retain such support? How did it manage to be such a tight election?

He put the public machine at the service of his election in a very criminal way, and with the support of the majority of the National Congress. So, he passed a provisional measure to release something like six billion dollars of cash aid on the eve of the elections. He also lowered the price of fuel and distributed the funds via a secret budget that the National Congress has invented – essentially using public money and resources without any transparency or parliamentary oversight.

He also used the gigantic machine of production and dissemination of fake news, really on an industrial scale, using mainly the evangelical churches as his tribunes to amplify the strength that he already had in the social networks, saying that Lula was going to implant communism in Brazil, that he would legalize abortion, that he would legalize all the drugs, that people who are in prison would all be released – things that are completely outside reality.

Days before the election, there was a lot of harassment. And the owners of the factories and the bourgeoisie in general threatened their employees, saying that if Lula won the election, they would be unemployed. On the day of the election they used the federal highway policy to block buses that were carrying people to vote in the regions where Lula is more popular, saying that they were auditing the conditions of the buses. They tried to avoid letting people get to the polling station.

In this context, the victory of Lula was really a very huge democratic victory. We are saying that it’s the most important democratic victory since the fall of the dictatorship that we had from 1964 to ’84 in Brazil, because it was really something very difficult to overcome, all these difficulties to win the election.

Could you tell us a bit about Lula, who narrowly defeated Bolsonaro? What were the program, the manifesto, or the proposals that Lula campaigned on? What were the positives and the weaknesses in his campaign?

Well, Lula had already governed Brazil for eight years – plus his PT successor, Dilma Rousseff, for more than six years. She was overthrown by a parliamentary coup [a legal maneuver aimed at removing the PT government which was backed by the right]. But they always governed with the bourgeoisie. He basically showed during the campaign that he would repeat this class-collaboration-government project from before. His choice of Geraldo Alckmin as vice-presidential running mate is a clear expression of this policy of collaboration with the bourgeoisie. Alckmin has governed São Paulo for many years, and he’s a representative of the São Paulo bourgeoisie, the most important section of Brazil’s bourgeoisie.

On the economy, Lula is completely tied to the neoliberal recipe. He is going to have a neoliberal economic policy. But he has also made some important promises during the campaign, like an adjustment of the minimum wage above inflation, emergency aid of 600 real (plus an added amount per child) to families, exemption of income tax for those who earn up to six thousand real per month (roughly $500, only slightly below the national average wage). He also promised to renegotiate people’s individual debt.

Also, Lula has talked about taxing the billionaires. He’s talked about corruption, which has been a big problem in Brazil, including in his previous government. And also the revision of the labor reform – a very bad reform that made employment very precarious and removed important rights. He also talked about strengthening the public universities by giving them more money and increasing access for low-income students.

So, he made some promises that are important to poor people, to the working class, to women’s rights, LGBT rights, Black people’s rights. It’s completely different from Bolsonaro and his behavior.

But we know it’s going to be a class-collaboration government. It’s clear in his program, and it’s clear in his alliance with Alckmin.

It’s going to be a government of bourgeois coalition, with some policies directed to the working class and poor people.

The situation is very complicated, because if Lula had not been the representative of a united front against the extreme right, had not made this coalition with the neoliberal progressive sector of the bourgeoisie, he wouldn’t have won the election. And we would probably be stuck with Bolsonaro.

But aren’t there elements of Bolsonaro’s base that are disenfranchised, poor people, working people that were turned off by Lula’s neoliberal policies? Could Lula have appealed to those layers of people with a more radical program – or was this just not on the cards?

We can’t demand Lula to be what he’s not. He’s not this kind of left politician anymore. So that’s the debate we have inside PSOL, because we in MES think that PSOL shouldn’t be in the government. We have to be independent, so that we can be a subversive left that tries to get support from these people that have voted for Bolsonaro because they are fed up with the establishment. They don’t trust the justice system, they don’t trust the politicians, they don’t trust the Congress. And they saw Bolsonaro as a person who is external to the system, although he’s not. He’s a rotten part of the system. But he tried and he managed to appear like someone outside of the system.

So we need to be a subversive left that is in the streets, that is at the demonstrations, that is demanding the rights of the people. That is how we can build support.

Around the time Dilma was impeached, PSOL also had debates about what its role should be. We [in MES] stood for calling new elections, because Dilma had lost the support of the people, because she was running a neoliberal government attacking people’s living standards and rights. So, she had lost the support of the working class, and the right wing came with all its strength to try to throw her out of the government.

PSOL didn’t call for elections. The government didn’t call for elections. This process of division – Dilma is good, she has to stay, or no, Dilma is bad, she has to go – gave Bolsonaro a lot of strength. The Left, including PSOL, all stayed with Dilma. That was, in our [MES’s] opinion, a mistake. PSOL should have been against the impeachment, but should have called for new elections, because that would be the democratic solution to the lack of support that Dilma had at that moment.

So now there is again a debate inside PSOL about how to act and how to relate to the government.

Can you tell us a bit more about PSOL and how it originated?

We founded PSOL at the end of 2003, when I and three other members of parliament were expelled from the Workers’ Party, PT. I was a member of the national parliament. We had a senator, Heloísa Helena. Later on she ran for president in 2006 representing PSOL. We were expelled from the PT because we refused to vote in favor of a pension reform that Lula put forward which was very aggressive against the public servants. That was a very different situation from today. When we started to build PSOL, we had to affirm the need to build an anticapitalist alternative amid all the frustration that was caused by Lula’s rapid turn to the right.

In 2003, unlike today, there was an expectation that Lula would run a really left government. But he was rapidly moving to the right. The pension reform was the culmination of this, but when he appointed his ministers, he had already chosen a lot of bourgeois representatives. So, the bourgeois character of the government was becoming clear from the beginning, and we had to leave the Workers’ Party because we couldn’t be in the party that had transformed into a manager of bourgeois interests in the government. So we had to build an anticapitalist alternative.

PSOL has grown a good bit in recent years. In the Chamber of Deputies elections, I think you rose this year to over 4 percent, with over 4.6 million votes, right?

Yes, we now have ten members in the national parliament, and also in the regional parliaments, but we still have a lot of work to do. We have to penetrate the sectors that are targeted by Bolsonarism, such as the low ranks of the security forces, the military, and the more traditional working class in the industrial poles. We are weak in these sectors and amongst the very poor people. PSOL is strong in the universities, among the youth, and in the sectors of the working class that are more organized. But we have to be more organized in the places where people are struggling for life – in the slums, in the big cities.

The threat of the far right hasn’t disappeared. What can be done to fight the far right?

First, demanding from Lula’s government to fulfill his promises and make changes to the benefit of the working class. This is very important to stop the extreme right from capturing all the support from people who are discontented with the government.

We need to have a dialogue with the anti-establishment feeling that we were talking about before. It has fueled Bolsonarism, this anti-regime feeling. So, we need to sound a note of discord and subversion as we defend the needs of the people, to build a revolutionary left that can show that it’s not through the establishment that our problems will be solved, that it’s necessary to have a more radical alternative on the left.

We also have to penetrate into the sectors that I mentioned before, mainly the police, because the police are a real stronghold of Bolsonaro’s extreme right. We are starting to reach them in my state – I received many votes from the lower ranks of the police because I supported them in their fight for a career – but it’s an isolated case, I would say. We have to make this experience more national.

And it’s also important to prosecute, judge, and punish Bolsonaro and all the politicians, all the entrepreneurs and the public agents that have committed crimes during this government, violating laws and violating the constitution. Bolsonaro, especially, must be judged for his crimes. And right now, at this moment, the extreme right is still in the streets of Brazil demanding a military intervention, saying that the elections were fraudulent, and they are completely rejecting the result of the election because they don’t accept that Bolsonaro has lost. They are threatening people who have voted for Lula with unemployment. So we have to go after these people and prosecute, judge, and punish them.

So Bolsonaro is gone, but the struggle against Bolsonaro continues.

Exactly.

[only online:]

Read more of MES’s election analysis here:

Lula’s victory was a great democratic triumph against authoritarianism, statement by the MES National Executive: https://movimentorevista.com.br/2022/11/lulas-victory-was-a-great-democratic-triumph-against-authoritarianism/

Bolsonarism: investigate, judge and punish, by Luciana Genro: https://movimentorevista.com.br/2022/11/bolsonarismo-investigar-julgar-e-punir/

by

by